Types of Pancreatic Cancer vary in their origin, symptoms, progression, and treatment strategies. As one of the most aggressive and complex cancers, pancreatic cancer demands early recognition and tailored intervention. Whether you’re a patient, caregiver, or medical professional, understanding the distinctions between exocrine and endocrine pancreatic cancers is essential for making informed decisions. This guide breaks down the key characteristics, signs, and medical approaches for each type—empowering you with the knowledge to navigate diagnosis and treatment with clarity.

What Is Pancreatic Cancer?

Pancreatic cancer is a disease that begins in the cells of the pancreas—an essential organ nestled deep in the abdomen, just behind the stomach. Despite its small size, the pancreas plays a dual role in maintaining both digestive and hormonal balance. It contains two primary types of tissue: exocrine glands, which produce enzymes that help break down fats, proteins, and carbohydrates, and endocrine glands, which release hormones such as insulin and glucagon to regulate blood sugar levels.

Cancer of the pancreas develops when genetic mutations cause normal cells within the pancreas to grow and divide uncontrollably, forming a tumor. These tumors can interfere with essential pancreatic functions and, if left undetected, can invade nearby structures or spread to distant organs such as the liver, lungs, or peritoneum.

According to the American Cancer Society, pancreatic cancer accounts for approximately 3% of all cancers in the United States. However, it is responsible for about 7% of all cancer-related deaths, making it one of the deadliest malignancies. This disproportionate mortality is largely due to the asymptomatic nature of early disease and its tendency to spread quickly before diagnosis. Most patients are diagnosed at advanced stages, limiting the effectiveness of curative treatments.

While ongoing research is improving early detection and treatment strategies, pancreatic cancer remains a formidable health challenge requiring urgent attention, especially for individuals with known risk factors or a family history of the disease.

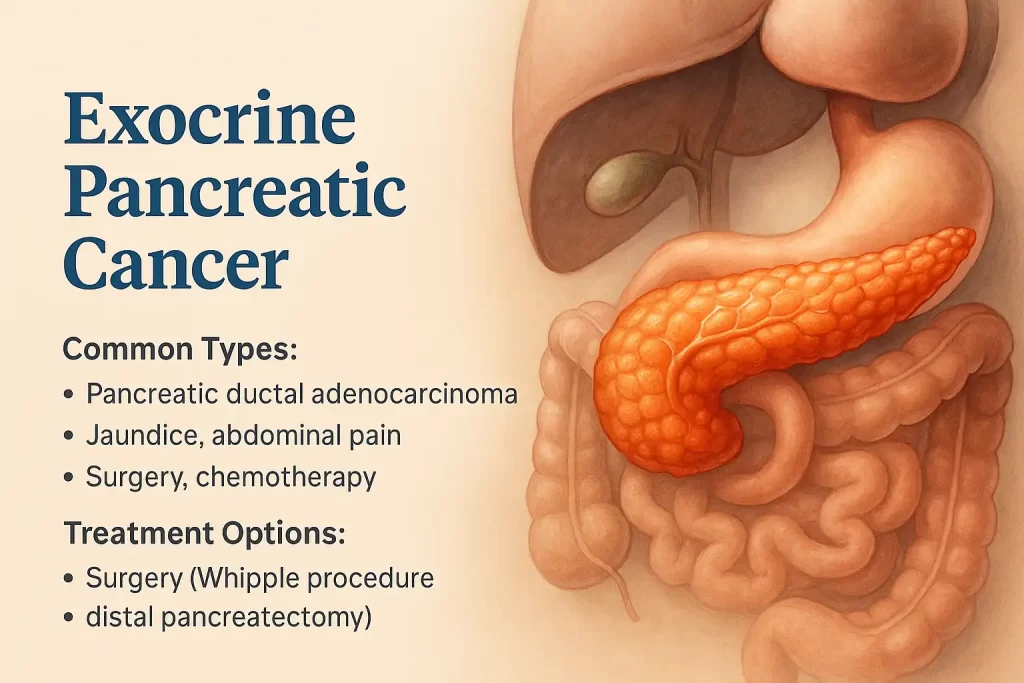

Exocrine Pancreatic Cancer

Definition:

Exocrine pancreatic cancer refers to malignancies that originate in the exocrine cells of the pancreas—the part responsible for producing digestive enzymes that are released into the small intestine. These enzymes are essential for breaking down fats, proteins, and carbohydrates in the food we eat. More than 90% of all pancreatic cancers fall into this category, making it by far the most prevalent form of the disease.

Common Types of Exocrine Tumors:

- Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma (PDAC):

This is the most common and aggressive type, originating in the lining of the pancreatic ducts. PDAC is typically diagnosed at a late stage and is associated with a poor prognosis. - Acinar Cell Carcinoma:

A rare form that arises in the enzyme-producing acinar cells. Though less common, it may secrete excess digestive enzymes, leading to unique clinical symptoms. - Pancreatic Cystic Neoplasms:

These include several subtypes such as serous cystadenomas and mucinous cystic neoplasms. Some are benign, but others have malignant potential and require surgical evaluation.

Symptoms:

Exocrine pancreatic tumors often present vaguely or remain asymptomatic in early stages, making early detection difficult. When symptoms do emerge, they may include:

- Jaundice: A yellowing of the skin and eyes, often due to bile duct obstruction.

- Persistent abdominal or back pain

- Unexplained weight loss and loss of appetite

- Chronic fatigue or weakness

- Digestive disturbances, such as greasy or pale-colored stools, nausea, or bloating

- New-onset diabetes, particularly in older adults with no prior history

These symptoms frequently overlap with other gastrointestinal conditions, which can delay diagnosis.

Diagnosis & Prognosis:

Exocrine pancreatic cancers are notoriously difficult to diagnose early, as they tend to grow silently and spread quickly. By the time symptoms prompt medical attention, the disease is often advanced.

Diagnosis typically involves a combination of:

- Imaging tests (CT, MRI, PET scans)

- Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) with biopsy

- Tumor markers such as CA 19-9 in blood tests

The prognosis for exocrine pancreatic cancer is generally poor, especially in metastatic cases. However, early detection dramatically improves survival rates, and ongoing advances in imaging and screening offer hope for earlier intervention.

Treatment Options:

Treatment for exocrine pancreatic cancer depends on the stage at diagnosis, the patient’s overall health, and tumor location. Options may include:

- Surgical Resection

- Whipple Procedure (Pancreaticoduodenectomy): Removes the pancreatic head, duodenum, bile duct, and part of the stomach.

- Distal Pancreatectomy: Involves removing the tail and body of the pancreas, often along with the spleen.

- Total Pancreatectomy: Removes the entire pancreas, leading to insulin dependence.

- Chemotherapy

- Common regimens include FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine-based combinations, aimed at reducing tumor burden and improving survival.

- Radiation Therapy

- Used in combination with chemotherapy (chemoradiation) to shrink tumors or manage symptoms.

- Targeted Therapy / Immunotherapy

- Emerging treatments such as PARP inhibitors (for BRCA-mutated tumors) or immune checkpoint inhibitors may be used in select patients based on molecular profiling.

Endocrine Pancreatic Cancer (PNETs)

Also referred to as pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs), endocrine pancreatic cancers originate from the hormone-producing cells of the pancreas, specifically within clusters known as the islets of Langerhans. These cells are responsible for releasing critical hormones such as insulin, glucagon, and somatostatin directly into the bloodstream, regulating key metabolic functions—most notably, blood sugar levels.

Though PNETs account for less than 10% of all pancreatic cancers, they represent a clinically distinct category—often slower-growing and with markedly different symptoms and treatment approaches compared to exocrine pancreatic cancers.

Common Types of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors

Each PNET is classified by the type of hormone its tumor cells secrete. Some of the most recognized forms include:

- Insulinomas:

These tumors produce excessive insulin, leading to frequent episodes of hypoglycemia (low blood sugar). Symptoms may include confusion, sweating, dizziness, and fainting. - Glucagonomas:

Characterized by the overproduction of glucagon, these tumors often cause high blood sugar (hyperglycemia) and may be associated with migratory skin rashes, weight loss, and anemia. - Gastrinomas:

These tumors secrete excess gastrin, which stimulates acid production in the stomach. This can result in peptic ulcers, abdominal pain, and chronic indigestion (a condition often referred to as Zollinger-Ellison syndrome). - Somatostatinomas:

These rare tumors produce somatostatin, a hormone that inhibits several other hormonal pathways. Symptoms are often nonspecific but may include diabetes, gallstones, and digestive disturbances.

Notably, some PNETs are non-functional, meaning they do not secrete active hormones. These tumors may remain asymptomatic for longer and are often discovered incidentally during imaging for unrelated health issues.

Symptoms of PNETs

Unlike exocrine tumors, which typically produce mechanical symptoms such as obstruction or pain, PNETs often trigger hormonal syndromes due to excess secretion. Depending on the type of tumor, patients may experience:

- Recurrent low blood sugar (hypoglycemia)

- High blood sugar (hyperglycemia)

- Flushing, diarrhea, or cramping

- Skin rashes or ulcers

- Unexplained weight changes

- Digestive symptoms like indigestion or bloating

- Neuropsychiatric symptoms (in severe hormone imbalances)

These symptoms often mimic other endocrine or gastrointestinal conditions, which can delay diagnosis.

Diagnosis and Prognosis

PNETs are typically diagnosed through a combination of:

- Hormonal blood tests to measure levels of insulin, gastrin, and other peptides

- Cross-sectional imaging (MRI, CT scans)

- Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) for localized visualization and biopsy

- Nuclear medicine scans like Ga-68 DOTATATE PET/CT to assess somatostatin receptor expression

Unlike the more aggressive exocrine tumors, PNETs are often indolent, meaning they progress slowly. The prognosis varies widely depending on the tumor’s grade, size, functionality, and whether it has metastasized. Low-grade, localized PNETs may be managed conservatively or surgically, and many patients live for years—even decades—following diagnosis.

Treatment Options for Endocrine Pancreatic Cancer

Management is typically personalized based on tumor type, hormone secretion, size, and spread. Options include:

- Surgical Removal:

When feasible, surgery remains the cornerstone of treatment. Depending on tumor location, this may involve enucleation (removal of just the tumor) or partial pancreatectomy. - Targeted Therapies:

Drugs like everolimus and sunitinib are often used to slow tumor progression in patients with advanced disease. - Hormone-Blocking Therapy:

Somatostatin analogs such as octreotide or lanreotide help control hormone-related symptoms and may also inhibit tumor growth. - Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy (PRRT):

For certain patients, especially those with somatostatin-receptor positive tumors, PRRT offers a way to deliver targeted radiation therapy. - Active Surveillance:

In select cases, particularly with small, well-differentiated, non-functioning tumors, observation with regular monitoring may be the most appropriate approach.

Key Differences Between Exocrine and Endocrine Tumors

| Feature | Exocrine Tumors | Endocrine Tumors |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency | 90%+ of pancreatic cancers | Less than 10% |

| Growth Rate | Rapid and aggressive | Slower, can be indolent |

| Hormone Production | No | Yes |

| Common Symptoms | Jaundice, pain, weight loss | Hormonal effects (low/high sugar) |

| Main Treatments | Surgery, chemo, radiation | Surgery, targeted, hormone therapy |

Also referred to as pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs), endocrine pancreatic cancers originate from the hormone-producing cells of the pancreas, specifically within clusters known as the islets of Langerhans. These cells are responsible for releasing critical hormones such as insulin, glucagon, and somatostatin directly into the bloodstream, regulating key metabolic functions—most notably, blood sugar levels.

Though PNETs account for less than 10% of all pancreatic cancers, they represent a clinically distinct category—often slower-growing and with markedly different symptoms and treatment approaches compared to exocrine pancreatic cancers.

Common Types of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors

Each PNET is classified by the type of hormone its tumor cells secrete. Some of the most recognized forms include:

- Insulinomas:

These tumors produce excessive insulin, leading to frequent episodes of hypoglycemia (low blood sugar). Symptoms may include confusion, sweating, dizziness, and fainting. - Glucagonomas:

Characterized by the overproduction of glucagon, these tumors often cause high blood sugar (hyperglycemia) and may be associated with migratory skin rashes, weight loss, and anemia. - Gastrinomas:

These tumors secrete excess gastrin, which stimulates acid production in the stomach. This can result in peptic ulcers, abdominal pain, and chronic indigestion (a condition often referred to as Zollinger-Ellison syndrome). - Somatostatinomas:

These rare tumors produce somatostatin, a hormone that inhibits several other hormonal pathways. Symptoms are often nonspecific but may include diabetes, gallstones, and digestive disturbances.

Notably, some PNETs are non-functional, meaning they do not secrete active hormones. These tumors may remain asymptomatic for longer and are often discovered incidentally during imaging for unrelated health issues.

Symptoms of PNETs

Unlike exocrine tumors, which typically produce mechanical symptoms such as obstruction or pain, PNETs often trigger hormonal syndromes due to excess secretion. Depending on the type of tumor, patients may experience:

- Recurrent low blood sugar (hypoglycemia)

- High blood sugar (hyperglycemia)

- Flushing, diarrhea, or cramping

- Skin rashes or ulcers

- Unexplained weight changes

- Digestive symptoms like indigestion or bloating

- Neuropsychiatric symptoms (in severe hormone imbalances)

These symptoms often mimic other endocrine or gastrointestinal conditions, which can delay diagnosis.

Diagnosis and Prognosis

PNETs are typically diagnosed through a combination of:

- Hormonal blood tests to measure levels of insulin, gastrin, and other peptides

- Cross-sectional imaging (MRI, CT scans)

- Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) for localized visualization and biopsy

- Nuclear medicine scans like Ga-68 DOTATATE PET/CT to assess somatostatin receptor expression

Unlike the more aggressive exocrine tumors, PNETs are often indolent, meaning they progress slowly. The prognosis varies widely depending on the tumor’s grade, size, functionality, and whether it has metastasized. Low-grade, localized PNETs may be managed conservatively or surgically, and many patients live for years—even decades—following diagnosis.

Treatment Options for Endocrine Pancreatic Cancer

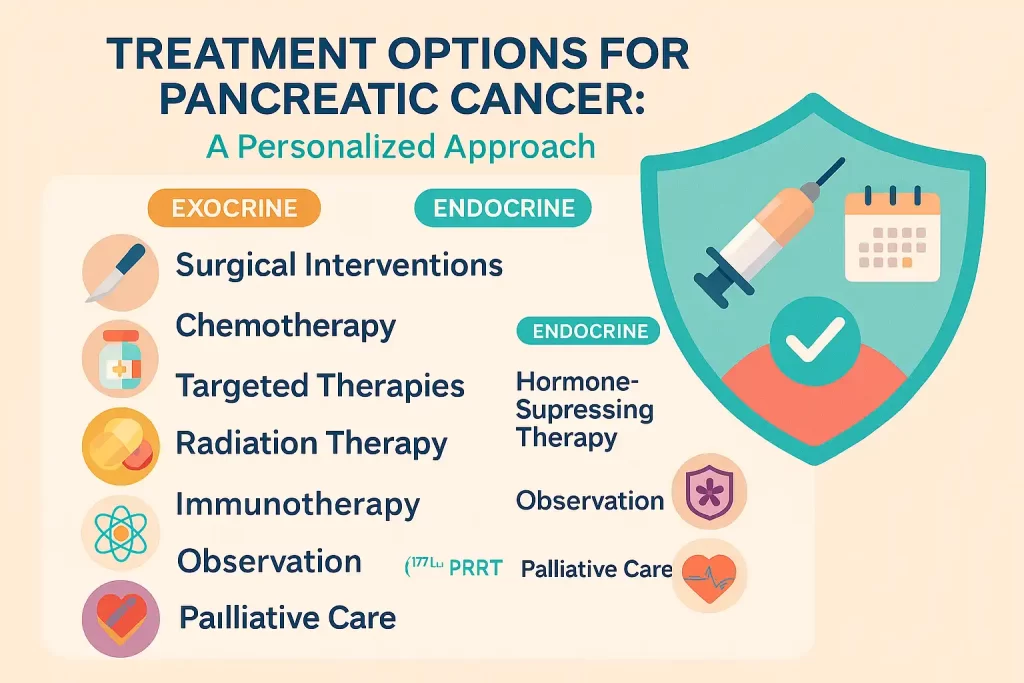

Pancreatic cancer treatment is not one-size-fits-all. The approach varies significantly based on the type of cancer (exocrine vs. endocrine), its stage at diagnosis, and the patient’s overall health and goals of care.

The primary treatment goals are to:

- Remove the tumor when possible

- Slow or stop cancer progression

- Relieve symptoms and improve quality of life

Let’s explore the most common and emerging treatment options, tailored to the specific type of pancreatic cancer.

🧬 1. Surgical Interventions

Surgery offers the best chance for a cure—but only if the tumor is localized and has not invaded nearby major blood vessels or distant organs.

For Exocrine Tumors (e.g., adenocarcinoma):

- Whipple Procedure (Pancreaticoduodenectomy):

The most common surgery for tumors in the pancreatic head. It involves removing part of the pancreas, duodenum, bile duct, gallbladder, and sometimes a portion of the stomach. - Distal Pancreatectomy:

Removes the tail and body of the pancreas, often along with the spleen. Used for tumors in the pancreatic body or tail. - Total Pancreatectomy:

Complete removal of the pancreas. While effective for widespread localized disease, it leaves the patient insulin-dependent.

For Endocrine Tumors (PNETs):

- Tumor Enucleation:

For small, well-defined tumors, especially functional ones like insulinomas, a focused removal may be sufficient. - Debulking or Cytoreductive Surgery:

In advanced cases with metastases, partial removal can reduce hormone-related symptoms and improve quality of life.

💉 2. Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy uses cytotoxic drugs to kill cancer cells or stop their growth. It is a mainstay for advanced or inoperable exocrine cancers and is sometimes used after surgery (adjuvant therapy) or before surgery (neoadjuvant therapy).

For Exocrine Tumors:

- FOLFIRINOX: A potent combination used for fit patients with advanced disease.

- Gemcitabine-based regimens: Often used for patients with more fragile health or as an adjuvant treatment.

For PNETs:

- Typically reserved for high-grade or poorly differentiated tumors, chemotherapy may include temozolomide, capecitabine, or streptozocin combinations.

🎯 3. Targeted Therapies

These treatments aim to disrupt specific molecular pathways that tumors rely on to grow.

Approved Options Include:

- PARP Inhibitors (e.g., olaparib) for BRCA-mutated pancreatic adenocarcinomas

- EGFR Inhibitors for certain exocrine tumors (limited effectiveness)

- Everolimus or Sunitinib for well-differentiated PNETs

These drugs tend to have fewer side effects than traditional chemotherapy but are only effective in genetically matched cases.

🧪 4. Hormone-Suppressing Therapy (for PNETs)

PNETs that produce excess hormones can be managed with:

- Somatostatin analogs (e.g., octreotide, lanreotide): Control symptoms like hypoglycemia or peptic ulcers and may slow tumor growth

- Interferon-alpha: Occasionally used to enhance the immune response

☢️ 5. Radiation Therapy

Radiation uses high-energy X-rays to destroy cancer cells. It is not routinely used for all pancreatic cancers but plays a role in:

- Local control for unresectable tumors

- Pain relief in advanced stages

- Combined with chemo for certain borderline resectable tumors

Techniques include external beam radiation, stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT), and intraoperative radiation in specialized centers.

💡 6. Immunotherapy

Still an emerging approach, immunotherapy helps the body’s immune system recognize and attack cancer cells.

- PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors (e.g., pembrolizumab) have shown some promise in tumors with microsatellite instability (MSI-high) or mismatch repair deficiency (dMMR)—mostly seen in rare cases of pancreatic cancer.

- Current trials are investigating vaccine-based and CAR-T therapies for more widespread application.

🔬 7. Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy (PRRT) – For Select PNETs

For tumors that express somatostatin receptors, PRRT delivers radiation directly to cancer cells using radiolabeled molecules. It’s approved for well-differentiated, metastatic, or inoperable PNETs and has shown encouraging survival benefits.

👀 8. Observation (“Watch and Wait”)

In some low-grade, non-functioning PNETs, especially those under 2 cm with no signs of growth or spread, active surveillance with regular imaging and labs may be appropriate—delaying treatment until there is evidence of progression.

🎗️ Palliative Care: Always an Option

For advanced cases where cure is not possible, palliative treatments aim to:

- Control pain and digestive symptoms

- Alleviate jaundice or obstructions (via stents or bypass surgery)

- Support emotional and nutritional health

Palliative care can be combined with active treatment and is not limited to end-of-life support.

How Doctors Diagnose Pancreatic Cancer Types

Diagnosing pancreatic cancer—and determining its exact type—is a complex process that requires a combination of advanced imaging, laboratory testing, and tissue analysis. Because exocrine and endocrine pancreatic tumors differ significantly in their behavior, origin, and treatment, identifying the precise type is essential for crafting an effective care plan.

Here’s a breakdown of the diagnostic tools used to evaluate suspected pancreatic cancer:

🖥️ Imaging Tests: Mapping the Anatomy

Initial evaluation often begins with non-invasive imaging, which helps detect the presence, size, and location of a tumor—and whether it has spread to nearby structures or distant organs.

- CT Scan (Computed Tomography):

A contrast-enhanced, multiphase CT scan is typically the first-line imaging modality. It provides high-resolution, cross-sectional views of the pancreas and surrounding tissues. It can also detect liver metastases or vascular invasion. - MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging):

MRI offers enhanced soft tissue contrast and is particularly useful for evaluating cystic lesions or liver metastases. When used with MRCP (Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography), it provides a detailed view of the pancreatic and bile ducts. - PET Scan (Positron Emission Tomography):

Often combined with CT (PET/CT), this test detects metabolic activity of cancer cells, helping assess the extent of disease or evaluate how the cancer is responding to treatment.

📡 Endoscopic Ultrasound (EUS): Precision From Within

EUS combines endoscopy with ultrasound imaging, allowing physicians to get very close to the pancreas via the stomach or small intestine. It offers:

- High-resolution images of even small or early-stage tumors

- The ability to perform a fine-needle aspiration (FNA) during the same procedure to extract cells or tissue for biopsy

- Essential information about lymph nodes and vascular involvement

EUS is often considered the most sensitive test for identifying small pancreatic masses.

💉 Blood Tests: Tumor Markers and Hormone Levels

Blood tests can provide crucial biochemical clues, particularly for screening, monitoring treatment, or detecting recurrence.

- CA 19-9 (Carbohydrate Antigen 19-9):

This is the most commonly used tumor marker for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (exocrine cancer). While not diagnostic on its own, elevated CA 19-9 levels can support clinical suspicion and track disease progression. - Chromogranin A, Insulin, Glucagon, Gastrin, and Other Hormones:

These markers are more relevant for endocrine tumors (PNETs). Hormone levels in the blood can reveal the presence of functional tumors such as insulinomas or gastrinomas before imaging even detects a mass.

🔬 Biopsy: Confirming the Diagnosis

While imaging and lab work can raise strong suspicion of cancer, a biopsy is typically required to confirm the diagnosis and determine the histologic subtype.

- Fine-Needle Aspiration (FNA):

Performed under EUS or CT guidance, this minimally invasive procedure extracts cells from the tumor. - Core Needle or Surgical Biopsy:

Provides more tissue when needed for molecular testing or to distinguish complex tumor types.

Once tissue is obtained, pathologists examine the cells under a microscope, often applying immunohistochemical staining to differentiate between exocrine and endocrine origins. Genetic and molecular testing may also be done to evaluate for actionable mutations, such as BRCA, KRAS, or MEN1, which can influence treatment strategies.

In summary: Diagnosing pancreatic cancer is a stepwise process that goes beyond merely identifying a mass. It requires a combination of high-resolution imaging, minimally invasive procedures, blood work, and pathology to accurately determine the cancer’s type, stage, and optimal treatment path.

When to See a Doctor

One of the most difficult aspects of pancreatic cancer is that it often remains silent until it reaches an advanced stage. Because early symptoms can be vague, nonspecific, or mistaken for common digestive issues, many individuals delay seeking medical advice—sometimes until the cancer has already spread.

That’s why understanding when to seek medical attention is a critical step in improving early detection and outcomes.

🚨 Key Symptoms That Warrant Medical Attention

You should contact a healthcare provider promptly if you experience any of the following persistent or unexplained symptoms:

- Jaundice

A yellowing of the skin or whites of the eyes, often accompanied by dark urine or pale stools. This can signal a bile duct obstruction caused by a pancreatic tumor. - Unexplained Weight Loss

Losing weight without changes in diet or activity level may indicate a metabolic issue linked to cancer or hormonal imbalance. - Upper Abdominal or Back Pain

Persistent discomfort in the upper abdomen that radiates to the back is a red flag, especially when not relieved by position or medication. - Changes in Stool or Digestion

Oily, pale, or floating stools may indicate poor fat digestion, which can occur when the pancreas is compromised. Nausea, bloating, or indigestion that doesn’t resolve should also be investigated. - New-Onset Diabetes

Adults over 50 who develop type 2 diabetes without traditional risk factors may warrant pancreatic evaluation—especially if paired with other symptoms. - Fatigue and Weakness

Chronic tiredness, especially when paired with other signs, could reflect systemic inflammation or tumor-related metabolic changes.

🧬 When Risk Factors Call for Extra Vigilance

Even in the absence of symptoms, certain individuals should maintain a proactive relationship with their doctor—especially if they have:

- A family history of pancreatic cancer or related genetic syndromes (e.g., BRCA2, Lynch syndrome, Peutz-Jeghers)

- A personal history of chronic pancreatitis, diabetes, or obesity

- Exposure to environmental toxins (e.g., certain chemicals in metalworking or dry cleaning)

- A racial background associated with higher incidence rates, such as African American or Ashkenazi Jewish heritage

🧪 The Role of Preventive Consultation

There are no standard screening guidelines for the general population. However, individuals with a strong family history or genetic predisposition may qualify for genetic counseling and surveillance programs, which could include regular imaging and blood work.

If you’ve noticed unusual symptoms or believe you’re at increased risk, don’t wait for the symptoms to worsen. Early discussion with a healthcare provider can lead to earlier intervention—and in some cases, lifesaving treatment.

Summary

Understanding whether a pancreatic tumor is exocrine or endocrine significantly influences treatment and prognosis. While exocrine cancers are more common and aggressive, endocrine tumors often offer more time for intervention. With advancing diagnostics and personalized therapies, earlier detection and better outcomes are becoming more achievable.

If you or someone you know is experiencing symptoms, consult a healthcare professional promptly.

FAQs

What is the most common type of pancreatic cancer?

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, an exocrine tumor, accounts for over 90% of cases.

Are endocrine pancreatic tumors cancerous?

Some are benign, while others are malignant. Diagnosis and grading determine severity.

Can pancreatic cancer be cured?

If detected early and surgically removed, some cases can be cured, especially certain endocrine tumors.